The Powerful Ghosts of the Fed Influencing Jerome Powell

The ghosts of Arthur Burns and Paul Volcker hold more power than almost all living Fed members

In the halls of the Eccles Building (U.S Federal Reserve HQ) in Washington DC, a ghost walks the halls, but holds more power than pretty much anyone in the world of U.S monetary policy aside from Fed Chairman Jerome Powell.

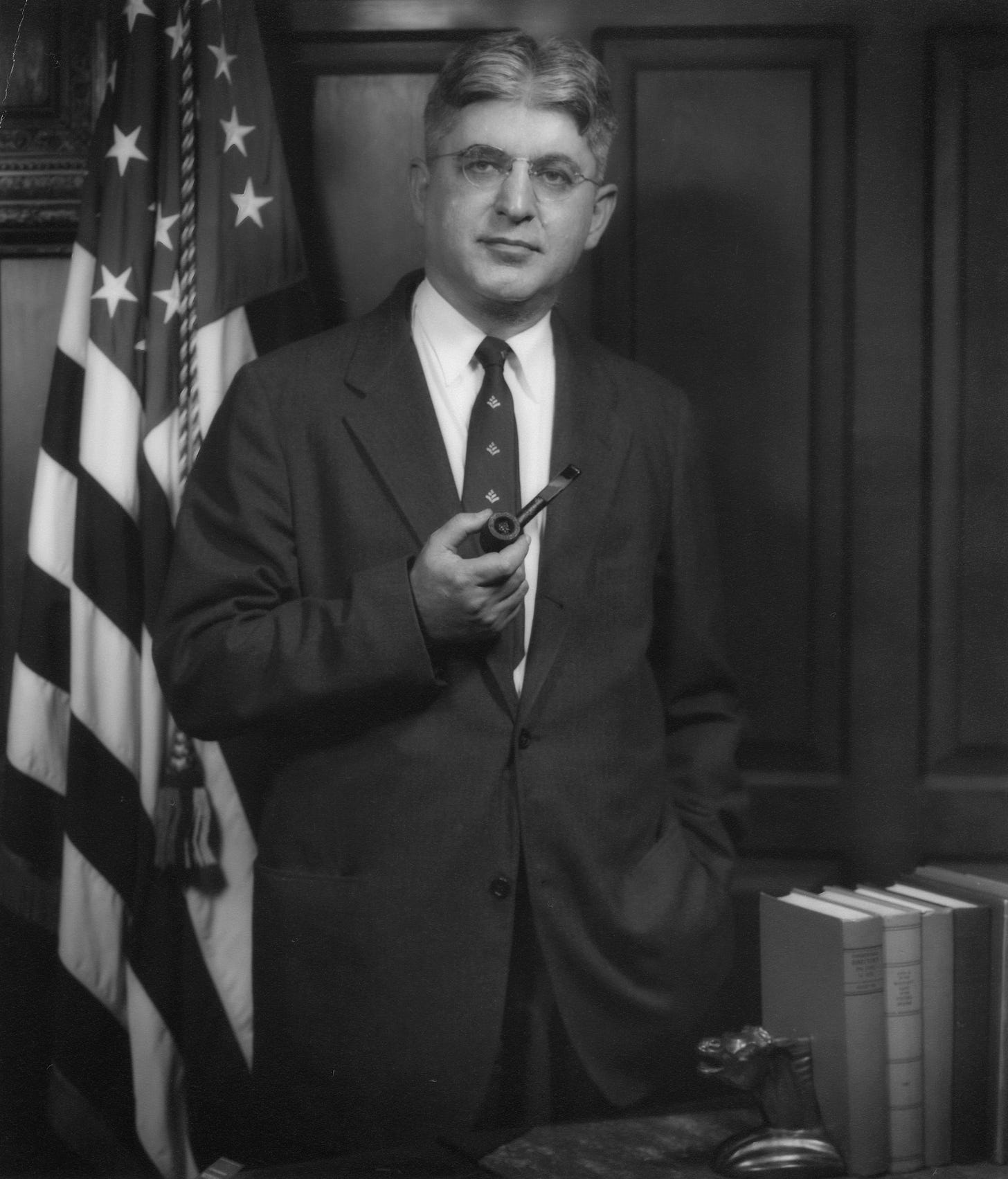

The ghost is the memory of former Fed Chairman Arthur Burns, who headed the Fed between January 1970 and March 1978. During this period high inflation became entrenched in the U.S economy and Burns became the defining cautionary tale for central bankers of what can happen if you don’t stay strong and keep rates high, even in the face of a recession.

In reality, the perception of Burns has turned into a bit of a meme rather than a fair critique of a leader confronted by challenges no one had to face before. That’s not to say that Burns didn’t make mistakes, he most certainly did, but despite the perceptions that define the ‘Arthur Burns Pivot’ meme, he actually stayed strong on inflation for a long time, even raising rates during a recession.

But why does this matter, what influence does the ghost of Fed Chairman’s past have on the present. Arguably quite a lot.

With Jerome Powell in what is almost certainly his final term as Fed Chairman, he is looking to secure a legacy and to go some ways to undoing some of the damage done to his reputation, in the hope that maybe just maybe he can be remembered alongside his hero Paul Volcker.

According to former Fed insider and Quill Intelligence CEO Danielle DiMartino Booth (a great Twitter follow by the way), Powell said in the middle of last year that:

“‘I don’t want to be the Second Coming of Arthur Burns,”

Its worth exploring what that actually means, because if its playing a significant role in guiding Powell’s actions, it could be key to understanding what the Fed may do with rates and reducing its balance sheet going forward.

The Life And Times Of Arthur Burns

Despite the widespread perception that Burns was a wet lettuce leaf of a Fed Chairman, when you look at his actions and the underlying data at the time, it becomes clear that he is actually a remarkably hard act to follow.

Before we go further its worth noting that the explicit 2% inflation target didn’t exist during Burns tenure, so his actions need to be seen in that context.

Prior to the 1973 inflation shock kicking off, Burns had raised rates from the lows of 3.75% following to the 1969-70 recession to 5.0%. Once it became clear that inflation was becoming a major issue he aggressively raised rates to 11.0% by August 1973.

To put this action into perspective, this was the highest Federal Funds Rate ever outside of the two world wars or the inflationary aftermath of troops returning home.

This is where Burns made a mistake, in September 1973 he slashed rates to 9.0%, despite headline inflation sitting at 7.0% and continuing to accelerate.

When he realized his mistake he raised rates to 13.0% over a period of 5 months during which the U.S economy was in the middle of a recession. Despite the recession and nine months of rising unemployment Burns held his nerve until finally he cut rates in the ninth month of the 1973-74 recession.

Its worth noting that not even the legendary 1980’s Fed Chairman Paul Volcker managed to equal Burns willingness to not only keep rates high, but raise them during a recession. During the two recessions Volcker headed the Fed through, he cut rates in month five of the 1980 recession and cut rates prior to the 1981 recession.

A Modern Context

As the banking crisis continues to rattle nerves throughout much of the world, there are increasingly loud calls for central banks and in particular, The Fed, to pause rate rises or even cut rates.

At the same time core inflation (the metric that central banks including the Fed tend to focus on) is running hot throughout much of the globe. In Japan, the most recent data had the highest reading in 40 years. In Europe, a record high in the history of the Eurozone was recorded in the last print. In Britain, core inflation unexpectedly reaccelerated, dashing hopes that it was in a downward trend.

For the U.S, the story is a little bit better, but not much. Core inflation is down from the peak of 6.6% recorded in September. But there is increasingly evidence that core inflation could be stabilizing around 5.5%. According to the Cleveland Fed’s Inflation ‘Nowcast’ projections, core inflation is expected to accelerate to 5.66% in March.

While a full blown financial crisis could change the calculus dramatically, for the time being most major central banks are trapped between high inflation and financial system woes.

If Powell were to pause, it would effectively invite comparisons with the meme version of Arthur Burns and risk a market rally driven by ideas that the Fed liquidity punch bowl and easy money may soon return.

If inflation were to remain stubbornly high following Powell’s pause, he would risk going down in history as yet another weak Fed Chairman who didn’t have the necessary courage to stay the course.

Going forward the ghosts of Volcker and Burns may be pivotal in driving the Fed’s decision making. Powell seemingly has a deep desire to salvage something of a positive legacy from his time as Fed Chairman and restore some much needed credibility to a deeply damaged organizational reputation.

Whether that will be enough to overcome a torrent of criticism from Capitol Hill and the howling of endless conga line of billionaire talking heads, who want their easy money back is another question.

Ultimately, the future of global monetary policy rests heavily on Jerome Powell’s shoulders. It is his actions that will be guide for other central banks, as they attempt to find a point where they can fight inflation and keep their banking systems intact.

In the long term that balancing act is not an easy one and that is putting it quite kindly.

— If you would like to help support my work by donating that would be much appreciated, you can do so via Paypal here or via Buy me a coffee. Regardless, thank you for your readership.

If you would like to support my work on an ongoing basis, you can do so here via Patreon or via Paypal here

No Fed chairman before or since was slower to cut extremely high rates mid-recession than Burns. When Volcker fans talk about Burns' wimpy policies of "the late seventies" that wasn't Burns. They are either referring to G. William Miller who was chairman from March 1978 to August 1979 (but pushed the funds rate well above 10%) or, more accurately, to Paul Volcker in 1980.

Volcker cut the funds faster and deeper than anyone before or since in 1980-- from over 18% to 9% in 3 or 4 months. Volcker eventually cut by 10 percentage points again from January 1981 to December 1982, but then put fed funds back up again in 1983 for reasons nobody can fathom.

https://twitter.com/AlanReynoldsEcn/status/1648426882327621634

Thanks for the read Tarric 👍