Rising Rates, 'Liar Loans' And Aussie Mortgage Holders In Trouble?

From different scenarios on rising rates to the cost of living, all by the numbers

As Australian interest rates continue to rise, so too does the level of anger directed at the Reserve Bank by some mortgage holders. From the RBA’s own Facebook page to numerous online forums and social media threads, the stories of households struggling to pay their mortgages after 1.35% worth of rate rises are legion.

There are naturally also households who have experienced a change in life circumstances which has effected their spending or incomes, which could be a major factor in the number of households expressing rising difficulty in paying their mortgage.

Then there is also the issue of the rapidly rising cost of living and falling real wages, which we’ll get into in some detail later in the article.

As one might imagine whether households are struggling to pay their mortgages or not is a matter of heated debate.

On one hand there is view that rates have only risen moderately and that households should be able to relatively easily pay their loans. In theory the required buffers from banking regulator APRA should ensure that a household can take a 2.5% increase in rates even at their loosest level, at the tightest a mortgage holder should be able to endure up to a 7.25% mortgage rate.

On the other, some say that households stretched themselves to the absolute limit and even these historically extremely low rates are enough to put major pressure on some borrowers.

Definitively quantifying exactly how widespread the households facing a high degree of difficulty paying their mortgages is challenging, but what we can do is explore some of the factors that are potentially contributing to this issue.

‘Liar Loans’

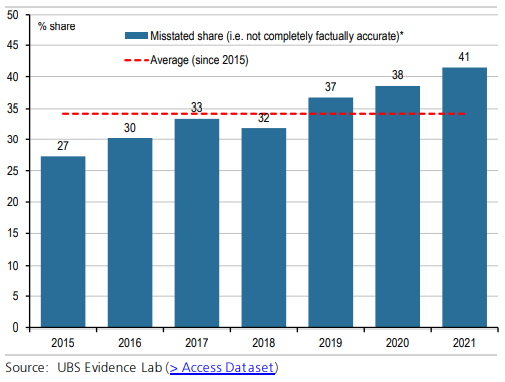

According to the annual UBS survey of home owners who took out a mortgage in the past year, 41% admitted to not being “completely factually accurate” on their mortgage application.

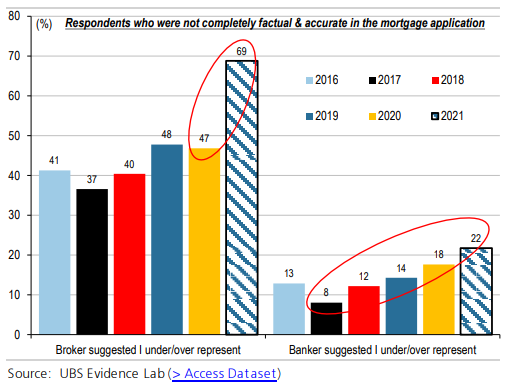

The most common areas of inaccuracy were under-representing living costs (34%), under-representing financial commitments (28%) and over-representing income (22%).

Of those who overstated their households income, 36% did so by over 25%.

While 31% of owner occupiers admitted to not being completely factually accurate, 53% of property investors did the same, along with 57% of those with two investment properties.

With over 40% of loans in 2021 potentially written under false pretences if the UBS survey is representative of the broader market, its not hard to imagine households who falsified their income or living expenses getting into trouble relatively swiftly.

In order to better explore this issue, lets do a bit of a case study.

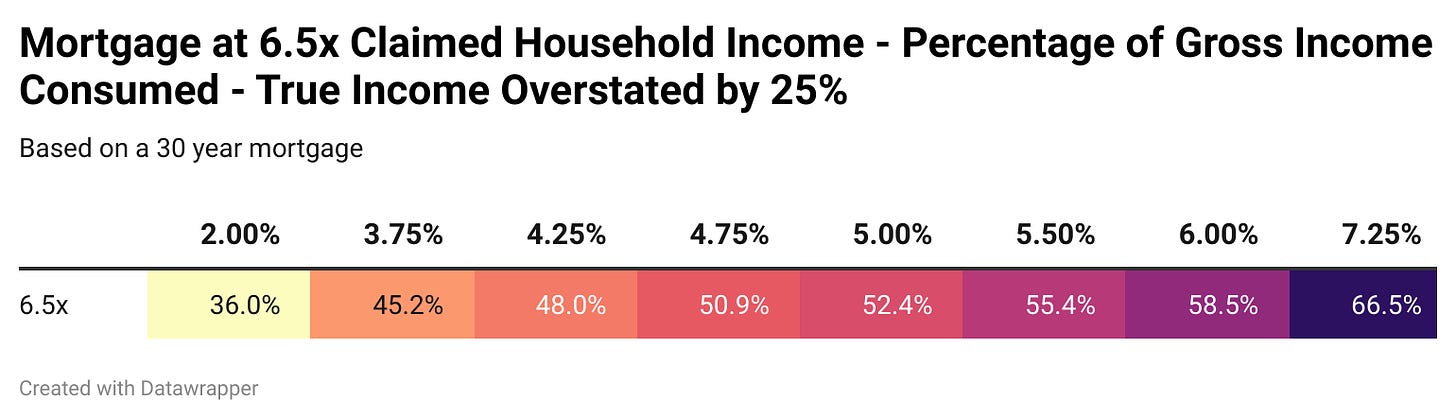

In this hypothetical example a household will have overstated their income by 25% and borrowed at a high debt to income ratio of 6.5x their claimed income. None of this is unprecedented based on the data, with up to 24.3% of loans during some periods written at more than 6x the household income of borrowers.

If you are interested in reading into the number of households who borrowed at high debt to income ratios and how they will be impacted by raising rates, I recently looked into this issue in detail here.

For this hypothetical household a loan at 6.5x their gross income at a 2% mortgage rate like those recently facilitated by the RBA’s term funding facility, would consume 28.8% of their claimed household income. However, it would be consuming 36% of their true household income.

While expending 36% of gross household income on mortgage repayments would put them in technical mortgage stress (more than 30% of gross income on their mortgage) and a challenging situation, its not an impossible scenario to cope with.

But when you start adding rising interest rates, this is where things start to swiftly get out of hand. Based on today’s 1.85% RBA cash rate, which translates to approximately a 4.25% mortgage rate (based on RBA numbers) the mortgage burden has already risen to 48% of gross household income.

Whether its a case of overstated incomes or understated expenses its easy to see how some of these households could rapidly find themselves in difficulty, even with interest rates still near record lows.

High Debt Loads and Rising Rates

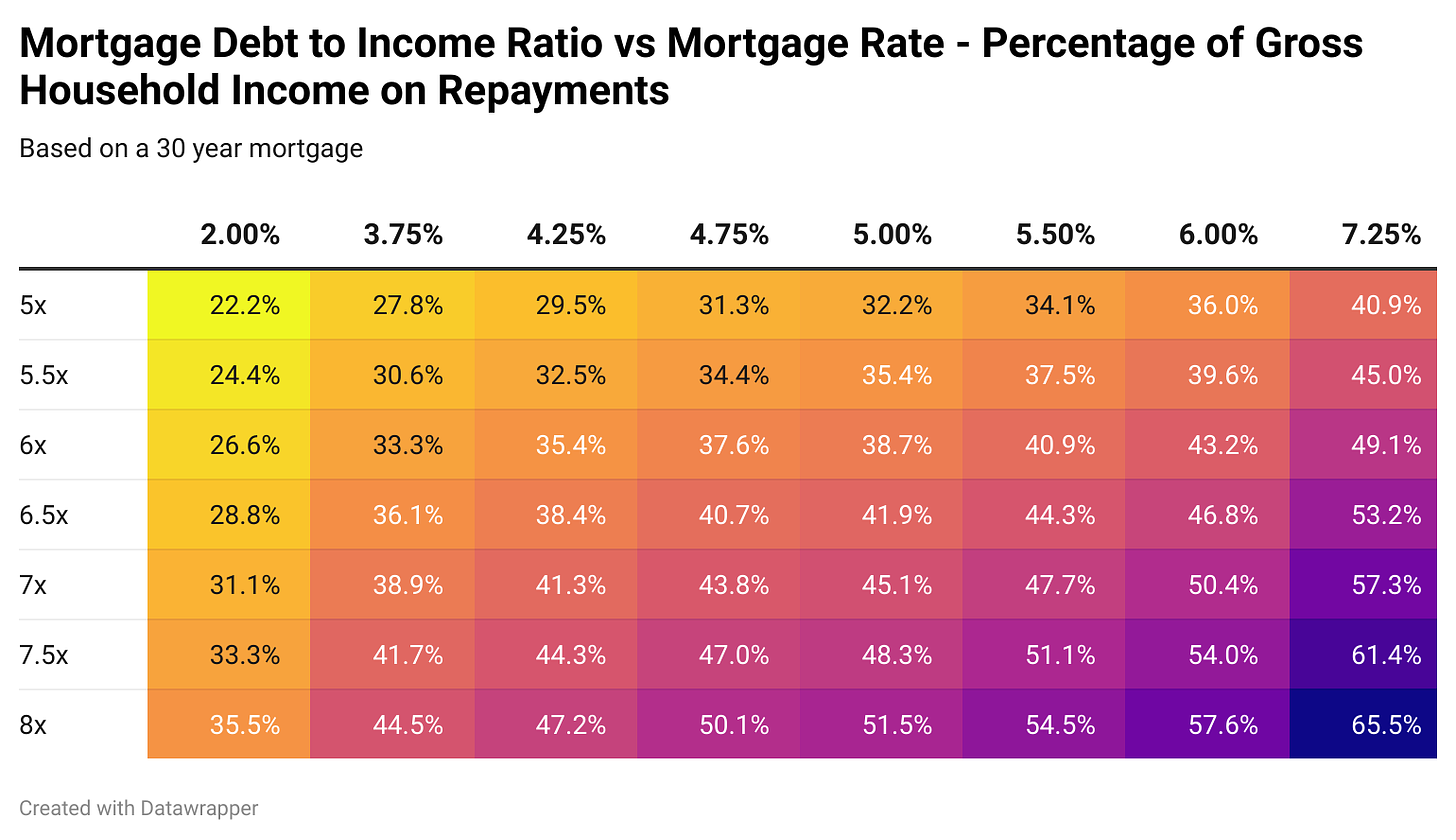

According to banking regulator APRA a high debt to income ratio is considered a loan written at more than 6x a households income. So in order to look at a cross section of buyers, we’ll be examining households that borrowed between 5 and 8 times their gross income.

Before we get to the numbers, its worth noting that under APRA guidelines mortgages are meant to have large buffers against interest rate rises built in, to ensure that borrowers don’t find themselves in trouble if rates rise.

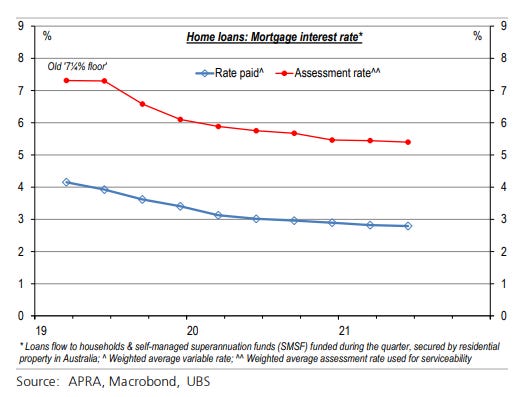

Under previous guidelines lenders were instructed to ensure that a borrower could pay their loan on a mortgage rate of up to 7.25%. In 2019, this was then reduced to a buffer of 2.5% on top of the loans actual rate, because reasons.

In October 2021, APRA then changed the serviceability buffer to 3% on top of the borrowers mortgage rate.

You can look at the data on the percentage of gross income being consumed at various mortgage rates and come to your own conclusion as to how realistic these serviceability buffers are.

For households who borrowed a relatively prudent 5x household income, they would not be in technical mortgage stress until mortgage rates hit 4.5%, which corresponds to an RBA cash rate of around 2% based on RBA data.

But once you get beyond that, this is where things start to get challenging. At a 4.25% mortgage rate which is approximately where we currently find ourselves once the rate rises have been fully passed on, all other borrowers we’re looking at are in technical mortgage stress.

For the borrower who rolled the dice on a loan at 8x their household income, they are already staring down paying almost half their gross income in mortgage repayments.

By the time the cash rate reaches 3.1%, which is APRA’s current buffer level households in the above scenarios would be paying on average between 34.1% and 54.5% of their gross household income on their mortgages.

With the market pricing in a 3.5% cash rate and several of the major banks predicting a peak of 3.35%, the burden of repayments could grow to be even greater than that.

Its also worth noting that the table above is based on a households debt being concentrated entirely in their mortgage, not in higher rate loans for cars or other purchases. So its entirely possible that the reality is significantly more challenging the table suggests for some households.

Rising Cost of Living vs Rising Rates

Since mentioning I would do this article, I have had quite a few comments suggest that the cost of living should be taken into account. While I am certain this will not entirely do the issue the justice it deserves due to the complexity of various disparate circumstances encountered by different households, we can at least put the issue into a degree of context based on the aggregate figures.

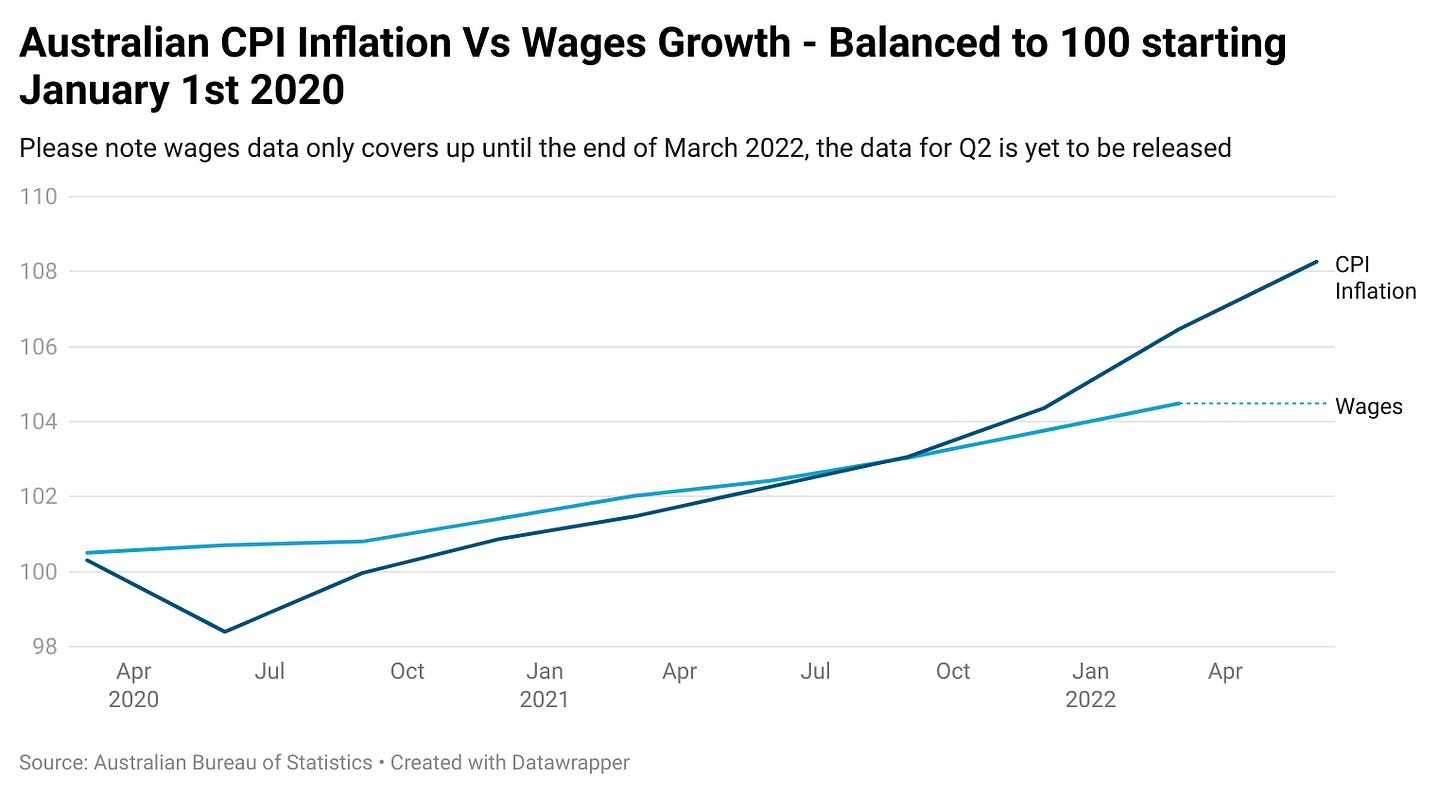

Since the start of 2020, inflation has risen by a cumulative 8.26%, while wages have grown by 4.49%. However, it is worth noting that due to the lag in reporting from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the data for wages growth only covers up to the end of Q1 this year, while the data for inflation covers up to the end of Q2.

For the sake of argument lets assume that these figures are broadly representative of where things sit today. The cost of living has outstripped wages growth by 3.77% based on where wages sat prior to the outbreak of the pandemic.

When contrasted with the impact of rising rates on mortgage holders, the relative blow it imposes on households very much depends on how much a household borrowed. For a household who borrowed 5x household income and has seen rates rise to 4.25% from a cheap introductory rate of 2%, they are now spending 7.3% more of their gross income on their mortgage.

For a household with a high debt to income ratio of 7x household income in the same rate scenario, they are now spending 10.2% more of their gross income on their mortgage.

Naturally there are households facing much greater than CPI increases to the cost of living and a sizable proportion of households who haven’t seen a pay rise, but both those issues are complex and better explored in far greater detail at a later date.

The Bottom Line

Looking at the issue purely from the context of APRA’s buffers, theoretically the number of people in difficulty at a 1.85% cash rate should be relatively minimal. But its also worth keeping in mind that buffers were in place for a 7.25% mortgage rate when households were out there borrowing 6x or more times household income.

Referring back to the previous heatmap chart of borrowers debt to income ratios vs repayments, you can make up your own mind on what level of gross income being expended on a mortgage is considered reasonable.

Ultimately, the issue isn’t just the RBA raising rates or even the rising cost of living, its also borrowers rolling off rates on to higher variable rates. While the cash rate has only risen by 1.75%, once you factor in rolling off a 2% loan to a 4.25% variable rate, the challenge becomes significantly greater.

In a vacuum, a reasonably prudent household who borrowed 5.5x their gross income would today find themselves in technical mortgage stress. For households who borrowed larger amounts relative to their income, the challenge would be even greater.

This brings us to the big question, could a 1.35% increase in the cash rate leave a significant number of households struggling to pay their mortgage?

The answer is very much a yes.

For households on high debt to income ratios of up to 8x, even a 1.35% cash rate could leave them paying up to 44.5% of their gross income on their mortgage. When you add in the average household falling behind the cost of living by 3.77% since the start of 2020, the challenge becomes even greater.

Since the start of 2020 alone more than 250,000 loans at a debt to income ratio of greater than six times household income have been written, so its not hard to imagine that a significant portion of borrowers who took on these loans face some degree of difficulty even with the cash rate where it sits today (1.85%).

While there is arguably a number of households venting frustration at rising rates amidst exaggerated claims of serious difficulty, the data clearly shows there are also households who are already facing a significant challenges as they attempt to service their mortgages.

— If you would like to help support my work by donating that would be much appreciated, you can do so via Paypal here or via Buy me a coffee. Regardless, thank you for your readership.

When you look at take home income it looks worse. It’s prob fair to assume 20% tax (for avg income), so the interest cost as percentage of actual income is much higher.