Rising Rates & Australia's Over-leveraged - A Powder Keg Of Risk

Some households face paying more than 50% of their gross income on their mortgage

When the pandemic arrived on Australia’s shores in the early part of 2020, the RBA swiftly cut interest rates to 0.25% and started its yield curve control program, which was designed to cap the 3 year government bond rate at 0.25%. This was later revised to 0.1% in November 2020 upon the RBA cutting the cash rate to 0.1%.

During this same period it also deployed a ‘Term Funding Facility’ (TFF) for the banks, which was basically $200 billion in funding over 3 years at 0.25%, this was later revised lower upon its final rate cut to 0.1%.

By the time the TFF had its last draw-downs, it had given $188 billion to the banks at just 0.1% interest, a rate the banks never would have been able to achieve on the open market.

This allowed banks to write unprecedentedly low rate loans, 3 year fixed rate loans at less than 2% became commonplace. Meanwhile variable rate loans were often offered at significantly higher interest rates, so the choice to take a fixed rate option was an increasingly appealing one.

By the end of 2021, just under 40% of all Australian mortgages were on a fixed term of some description, a huge transformation from the historically overwhelmingly variable rate loan book.

With sub-2% rates and the RBA ramming home month after month that it was “unlikely that interest rates would rise before 2024”, Australians not only piled into the market, but took on even more large loans relative to their income than ever before.

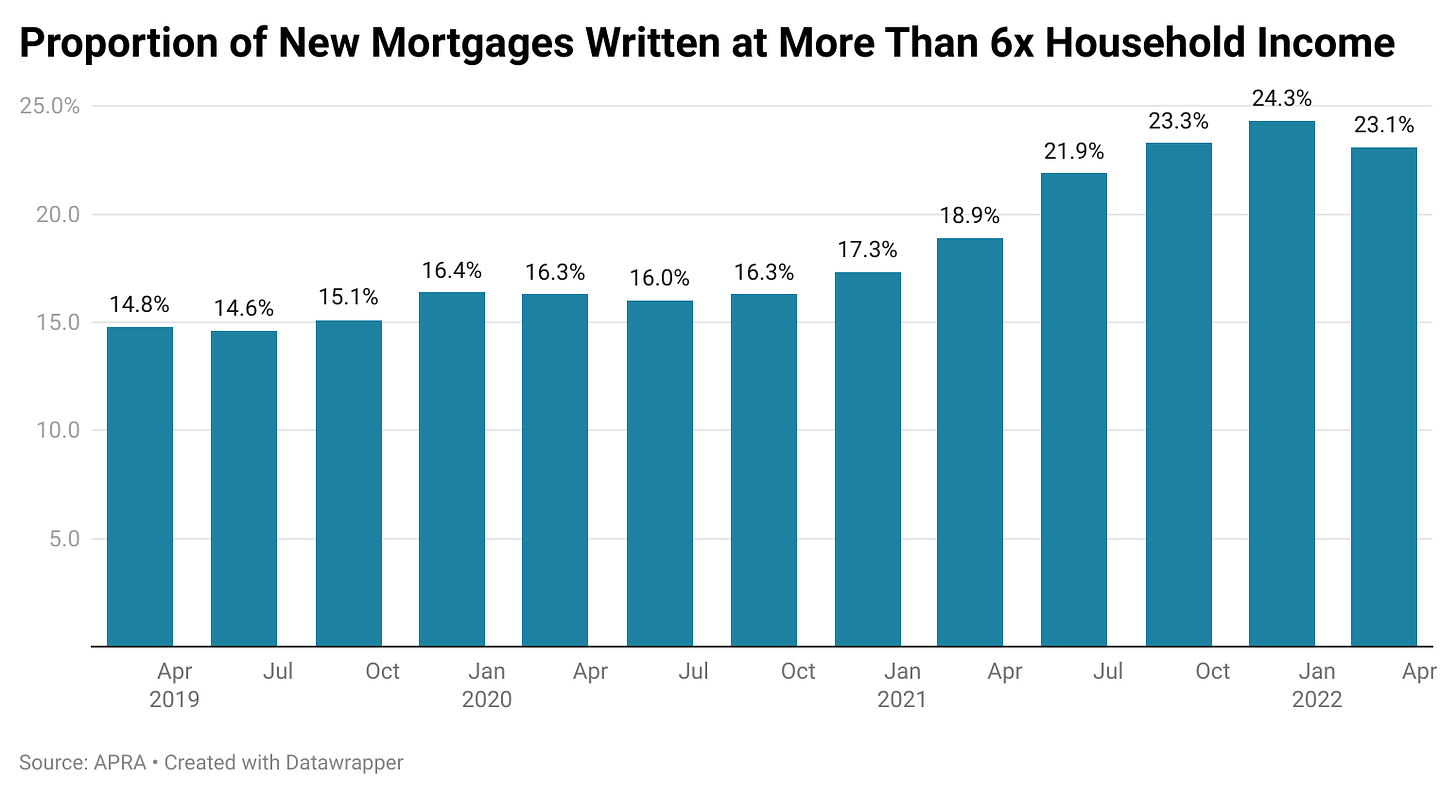

Prior to property prices taking off following the May 2019 federal election and the subsequent RBA rate cut in June 2019, 14.6% of new mortgages were written at a debt to income ratio of more than 6x.

Given the extremely cheap rates on offer and an atmosphere defined by narratives that rising rates wouldn’t be an issue for years to come, this figure then peaked at 24.3% of loans in the December quarter of 2021.

From the time the RBA slashed rates and started its yield curve control program, to the end of the March quarter of 2022, over 225,000 loans at a debt to income ratio of more than 6x household income were written. This figure will almost certainly rise to well over 250,000 when the figures for the June quarter are released in a few months time.

In order to better understand the risks for these households going forward, we’re going to look at some hypothetical case studies based on the absolute best case scenario of a 30 year mortgage.

Naturally the reality would be far more factors going against many of these borrowers, but for today we will be putting together a very conservative base case.

Our hypothetical household will be debt free aside from their mortgage and earn $100k per year (national household median is $90.7k).

Prior to the beginning of the current rate rise cycle, if you were to calculate a households borrowing power using a mortgage serviceability calculator from some of the major banks, it would come back with a figure of around 6.7-6.9x income.

With a recent survey performed on behalf of Finder.com.au showing that more than 1/3 of recent first home buyers were pushed beyond their budget in order to afford their home, we’ll be exploring the scenario of a household borrowing 6.8x of their income as one of our central themes.

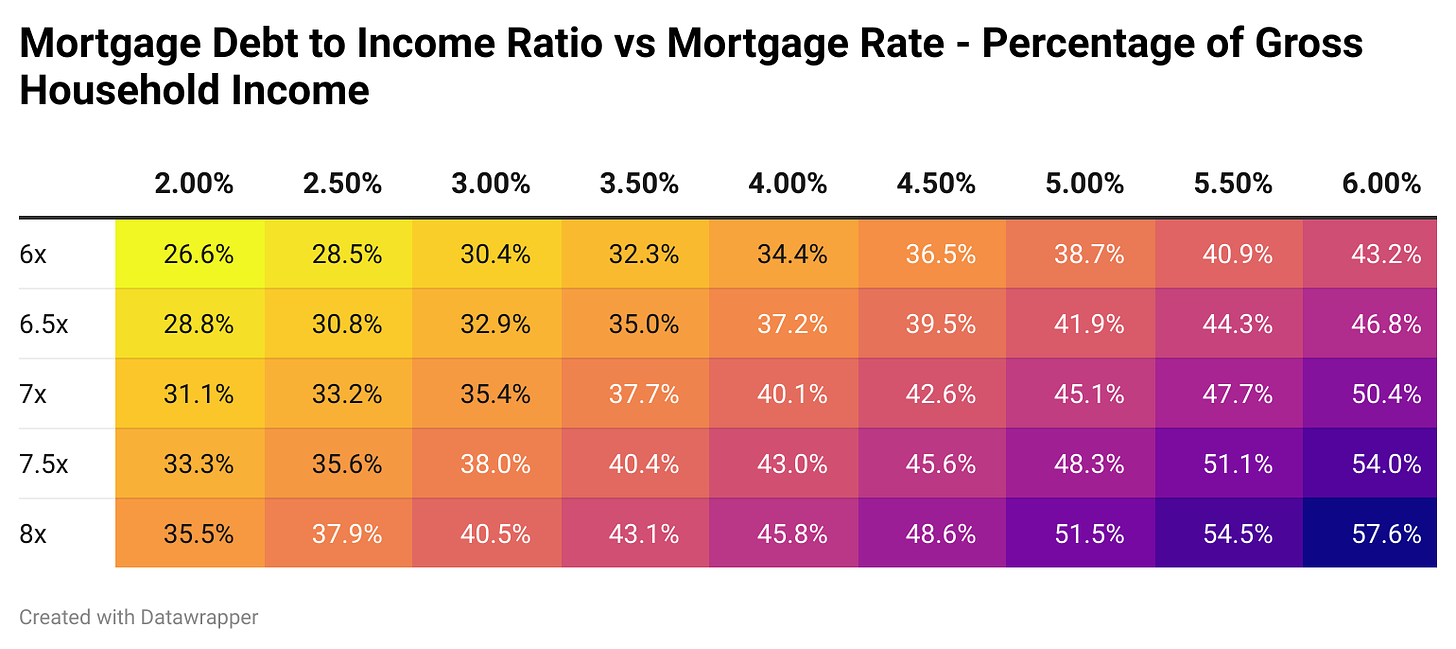

If this household borrowed 6.8x their household income on a 3 year fixed rate loan at 1.8%, this would consume 29.3% of their household income.

According to the RBA, prior to rates starting to rise the average mortgage rate on outstanding owner occupier loans was 2.5%. With the cash rate now having risen 1.25% and it widely tipped to rise another 0.5% in August, a mortgage rate of around 4.25% is likely to be roughly ballpark in the coming months.

At this level this would be consuming 40.2% of the gross income of our hypothetical household.

However, with the market pricing in a 3.5% cash rate peak for next year, this would put us at roughly the half way point of the interest rate rise cycle.

This view was recently shared by former Treasury Secretary Ken Henry during an interview with ABC’s 7:30 Report. During which he stated that the RBA will be looking to get the cash rate to a “more normal level of probably 3-3.5%”.

At a cash rate of 3.5% and a mortgage rate at roughly 6%, our hypothetical household would now be spending 48.9% of their gross household income on their mortgage.

Even in terms of the absolute best case scenario of a household borrowing exactly 6x their household income, at a 6% mortgage rate repayments would consume more than 43% of gross household income.

The Big Short Factor

If this is all starting to sound a bit like a film you’ve seen by the name of ‘The Big Short’, in very broad terms it is similar. A sizable proportion of borrowers have been encouraged to take out extremely low rate loans that will eventually revert to much higher rates.

This will no doubt prompt quite the case of sticker shock among impacted households staring down the barrel of interest repayments potentially more than tripling.

However, it is important to keep in mind that Australia is not the United States in 2008. Australia has full recourse loans, or in plain English, the bank can come after your other assets or even send you into bankruptcy. While in some U.S states, borrowers could simply mail the keys back to the bank and wash their hands of their mortgages.

Then there is the proliferation of what some economists and analysts came to call “Extend and Pretend”. During the early days of the pandemic, banks and regulators implemented this strategy where by mortgage holidays were given, bad loans were considered good and they just effectively hoped for the best.

Given the political nightmare that mass foreclosures would create in the event of a major recession and housing crash, its easy to see how this strategy could be implemented once more to keep owner occupier borrowers in their homes.

This would not be an unprecedented event, even outside of the pandemic. By the time of the tail end of the U.S housing crash, the banks had been bailed out and there was often little interest in foreclosing on homes that were deeply underwater.

The Back Drop

A scenario in which mortgage repayments rise to 43% of gross household income or more, was always going to be a challenging one, but once its put into the context of current circumstances, it becomes clear exactly how much pressure these households may find themselves under.

Currently Australia is in the midst of its longest period of negative real (inflation adjusted) wages growth since the introduction of the GST (goods and services tax) in the year 2000.

With the spending power of Australian households in aggregate falling behind the current rate of inflation by 2.7% per year and Treasury estimates that it will be 2024-2025 before wages growth begins to once again outstrip inflation, the challenge faced by mortgage holders who borrowed more than 6x household income will continue to grow in severity.

The Outlook

Perhaps one of the key takeaways from all of this is that these loans are not uncommon, we’ve seen more than a quarter of million loans written are more than 6x income in the past 2 years alone and as a proportion of overall lending, these types of loans peaked at almost 1/4 of all new loans.

The scenarios presented here are also relatively conservative ones, based on borrowing 6x income exactly and what a rough average of the banks borrowing power calculators would allow (6.8x household income).

Up until relatively recently borrowers were taking on loans at up to 9x household income at ANZ and NAB, but this was recently reduced to 7.5x and 8x respectively.

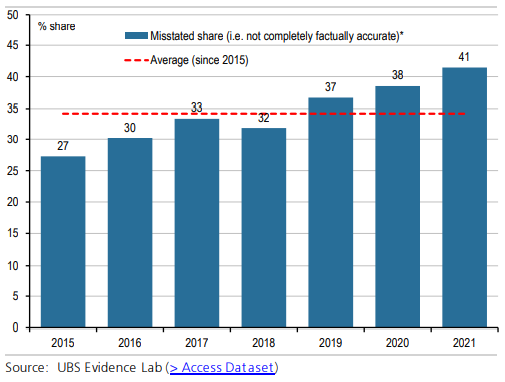

Yet as this particular story draws to a close we are yet to begin to explore the risks in non-bank lending and the impact of so called “liar loans”, where by some folks are less than truthful on their loan applications (41% of new loans in 2021 according to a survey from UBS).

Exactly what impact these arguably overleveraged borrowers will have on the housing market is challenging to determine, but suffice to say it won’t be positive. As we’ve seen in New Zealand prices can plummet all on their own without any assistance from stressed households pulling the ripcord and getting out of the market.

If rates do indeed rise to 3.5% as the market expects, the Albanese government, Reserve Bank and banking regulator APRA may yet return to a state of “extend and pretend”, keeping people in their homes even as mortgage repayments rise well out of reach for some households.

Ultimately, a loan at 6x household income or more was always a risky proposition for an individual household, with the cash rate returning to even half its long run average an extremely severe scenario.

In time this will present a significant challenge for these households if rates do continue to rise, but more than that it will force the banks and the government to do some soul searching on how to address this powder keg of risk in an inflationary environment.

— If you would like to help support my work by donating that would be much appreciated, you can do so via Paypal here or via Buy me a coffee. Regardless, thank you for your readership.

Interesting stuff and not without a precedent. Most bullish commentators say that comparisons to Oz now and Ireland 14 years ago are not valid. As someone who worked in real estate in Ireland during the height of the boom and then during the bust, I can tell you the comparisons are very valid and slightly scary. There were very little sub prime mortgages issued in Ireland, but there was lots and lots of very high debt to income mortgages available, up to 10 times income was not uncommon. In addition, the bank of mum and dad came to the help of many marginal borrowers because mum and dads property value increased dramatically in the early 2000’s. All of this in a relatively low interest environment in what was a booming economy, low interest rate due to being in the euro zone. Does this all sound familiar? The other thing people may not know is that the market was on the slide before the black swan of Lehman Bros came about. Before then banks started to slow down lending and before to long there were very few qualified house buyers. It was the lack of buyers that killed the market. The very few sales that occurred were by the marginal seller ie death, divorce etc, there were very few repos or openly bank forced sales. I can also tell you the extend and pretend by the banks in Ireland was immense and still going in some circumstances, I should know, as I was one of them.Sorry for the long comment, thought you might like the insight!

Great read Tarric. The ability to backstop the Banks and defend property prices has to become near impossible with falling commodity prices. AUD would collapse.