RBA Trapped Between The Fed And Rising Unemployment

As much as the RBA may want to cut, there would be a price to pay if the Fed remains resolute

Earlier this month, I posted an analysis on the Australian labour market warning that unemployment could swiftly rise as jobs growth slowed and labour force growth remained extremely high by historic standards.

With the release of the January jobs figures, those concerns were amplified as unemployment surged to 4.1% on a seasonally adjusted basis and hours worked fell sharply on both a seasonally adjusted and trend basis. This raises the possibility of a challenging scenario for the RBA, in which inflation remains elevated and unemployment rises far more swiftly than forecasted.

The revisions to prior data were just as unkind to the labour market, with trend hours worked growth compared with one quarter earlier now seen as collapsing to its lowest level since the depths of the 1990-1991 recession. In my previous piece, the drop on this metric had been -0.65%, December was revised to -1.29% and January recorded -1.40%.

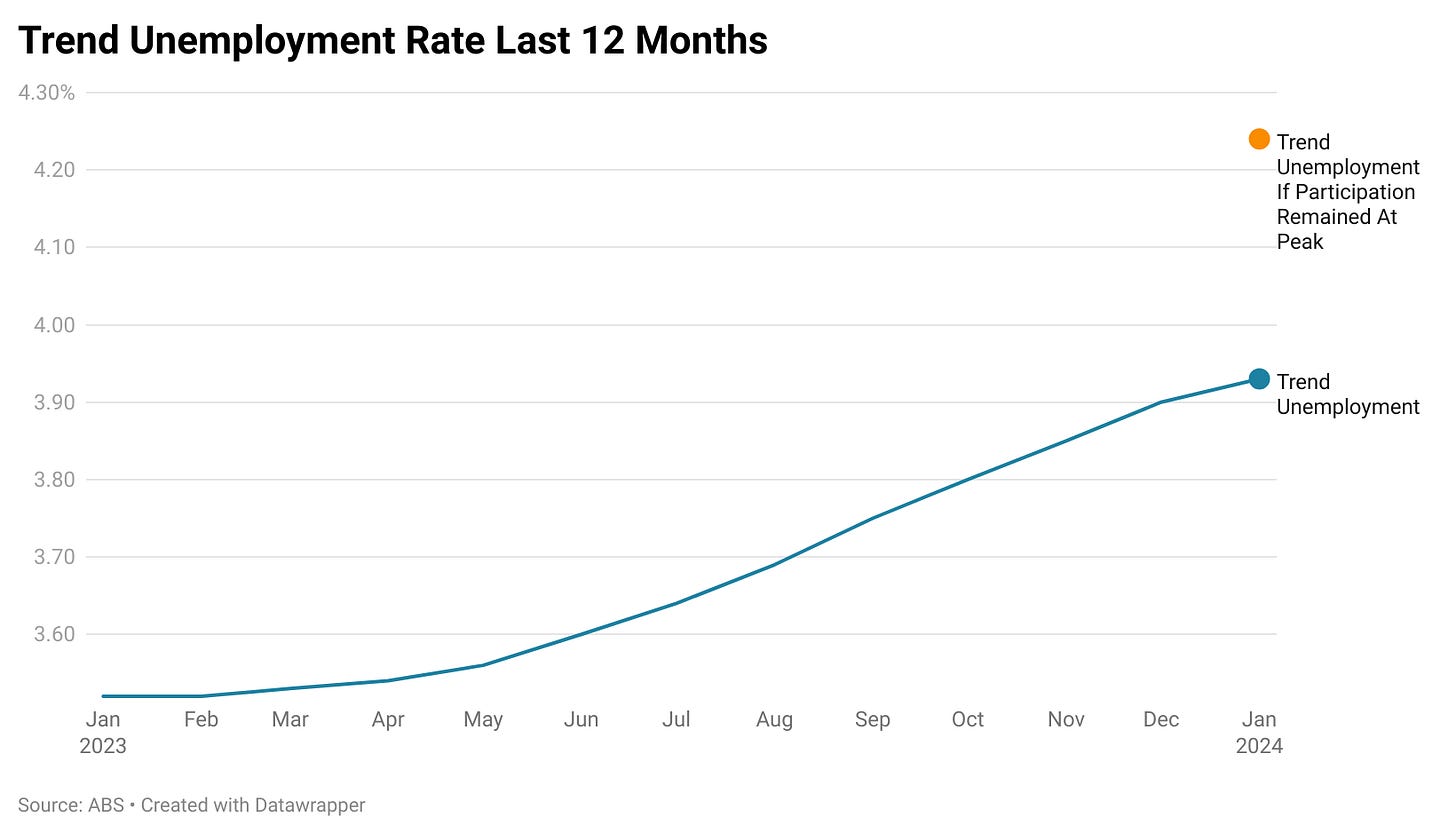

In terms of trend monthly jobs growth, the trajectory is quite clear. Considering that the labour market needs to create around 30,000 jobs per month just for unemployment to remain stable, the current level of jobs growth would see a relatively swift rise in unemployment if not the falling participation.

In this regard there is a fair bit of scope to cushion the blow at least theoretically. Prior to the pandemic the trend participation rate was 65.9%, today even after recent falls its 66.8%. To what degree this can act as a shock absorber given the ongoing issues with the cost of living remains to be seen, but the possibility is there.

Its worth noting that this is already playing a role in putting downward pressure on the unemployment rate. If not for declining participation, the trend unemployment rate would be over 4.2%

This brings us to the RBA. In recent weeks RBA Governor Michele Bullock has been relatively hawkish, making it clear that the fight against inflation is not done and that the middle of the target 2-3% band should be the organizations bullseye.

But with the possibility of a relatively swiftly deteriorating labour market, that may leave Governor Bullock and the rest of the RBA board stuck between a rock and a hard place. One imagines hopes were held in Martin Place that U.S disinflation would continue and that a slowing U.S economy would allow the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates.

By firing the starting gun for a major central bank rate cut cycle, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell would be providing scope to the RBA to follow suit if the board feel the need had arisen, without paying the potential price of additional downward pressure on the Australian Dollar.

But after an extremely strong jobs print which saw the U.S economy create 353,000 jobs and a CPI report which came in much hotter than expected across the board, the pricing of U.S rate cuts are now being pushed back to later in the year.

Historically, of all the major central banks, the RBA has arguably been the one most concerned with the labour market and minimizing job losses. Leading us to one of the big questions going forward, can the RBA afford to wait for the Fed?

The RBA’s forecast for the June quarter is 4.2%, for the December quarter 4.3% and 4.4% across the remainder of the estimates into 2025. With unemployment already at 4.1% and Michele Bullock’s personal neutral unemployment rate is at 4.5% (at which the labour market is not inflationary), Australia’s jobless rate may arrive at those targets much sooner than expected.

Historically, in the more 30 years of data on hand, the RBA has not chosen to go it alone cutting rates unless the RBA cash rate was much higher than the equivalent U.S Federal Funds Rate.

If this scenario of rising unemployment and a reticent to ease Federal Reserve does come to pass, the RBA would find itself trapped. On one hand it could hold off on cutting rates and wait for the Fed to fire the starting gun, thereby potentially allowing unemployment to rise further.

On the other, it could go it alone, break with history and the Fed, and accept the consequences that come from cutting out of step from the global benchmark for rates. If the U.S economy continues to hold up, there are risks of a weakening currency and in time imported inflation adding to the existing domestic inflationary pressures.

As hard as they may try and wish it wasn’t so, its possible this trap may not be avoidable for the RBA and they may be forced to make a choice between what they see as the lesser of two evils.

— If you would like to help support my work by making a one off contribution that would be much appreciated, you can do so via Paypal here or via Buy me a coffee.

If you would like to support my work on an ongoing basis, you can do so by subscribing to my Substack or via Paypal here