Long Term U.S Inflationary Pressures Becoming Entrenched?

Even moderate long term goods inflation could transform CPI inflation and by extension monetary policy

In recent weeks calls and predictions of the peak of U.S inflation have been coming thick and fast, from market legends and Wall St analysts alike.

But as the focus of the headlines is increasingly placed on inflation’s inevitable peak and falls back toward more normal levels, the underlying forces influencing U.S inflation are changing behind the scenes.

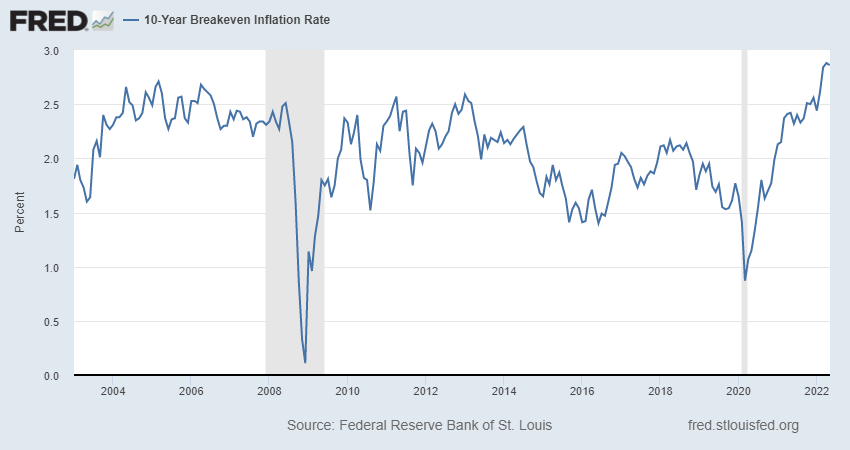

The U.S 10 year break-even inflation rate recently hit a peak reading of 2.98%, the highest level since comparable records began almost 20 years ago.

For those of you who may not be familiar with the metric, its effectively where the market believes annual inflation will sit over the next decade.

While there is a long list of possible reasons for inflation expectations effectively becoming unanchored, today I will be exploring two that could have a major impact on the future of U.S inflationary pressures, the decline of just in time supply chains and deglobalization.

But before we get into the details, its worth exploring what actually drove U.S inflationary pressures prior to the pandemic.

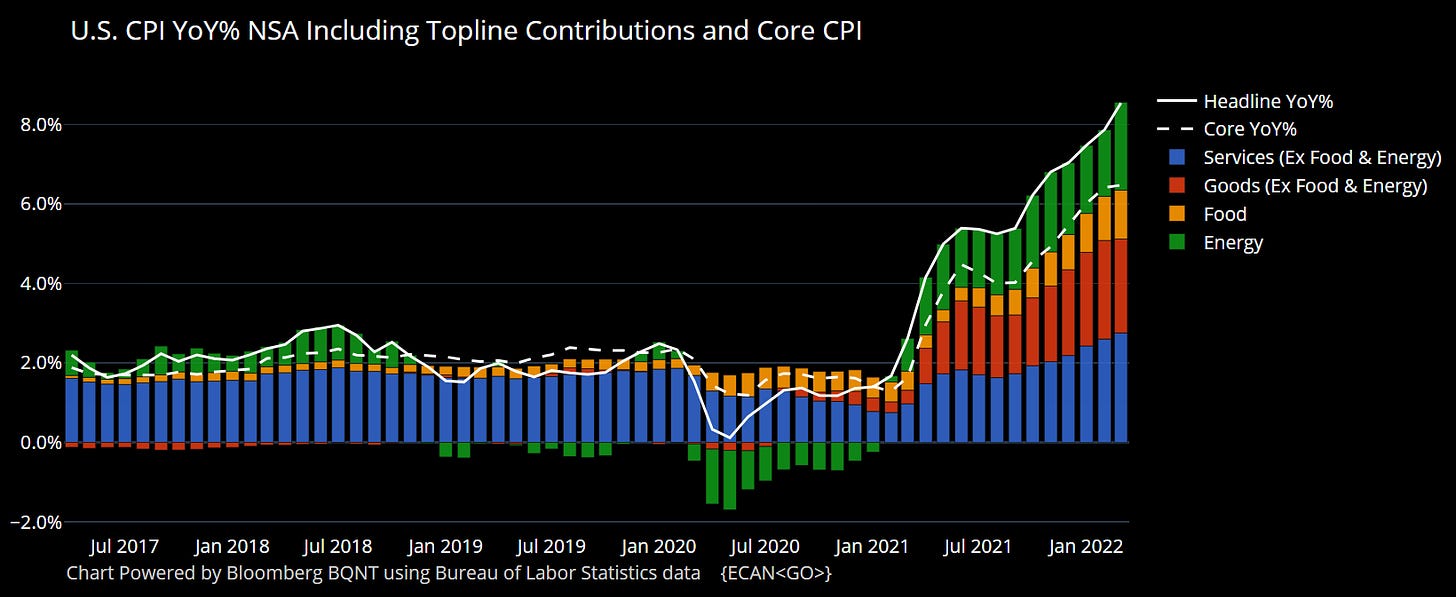

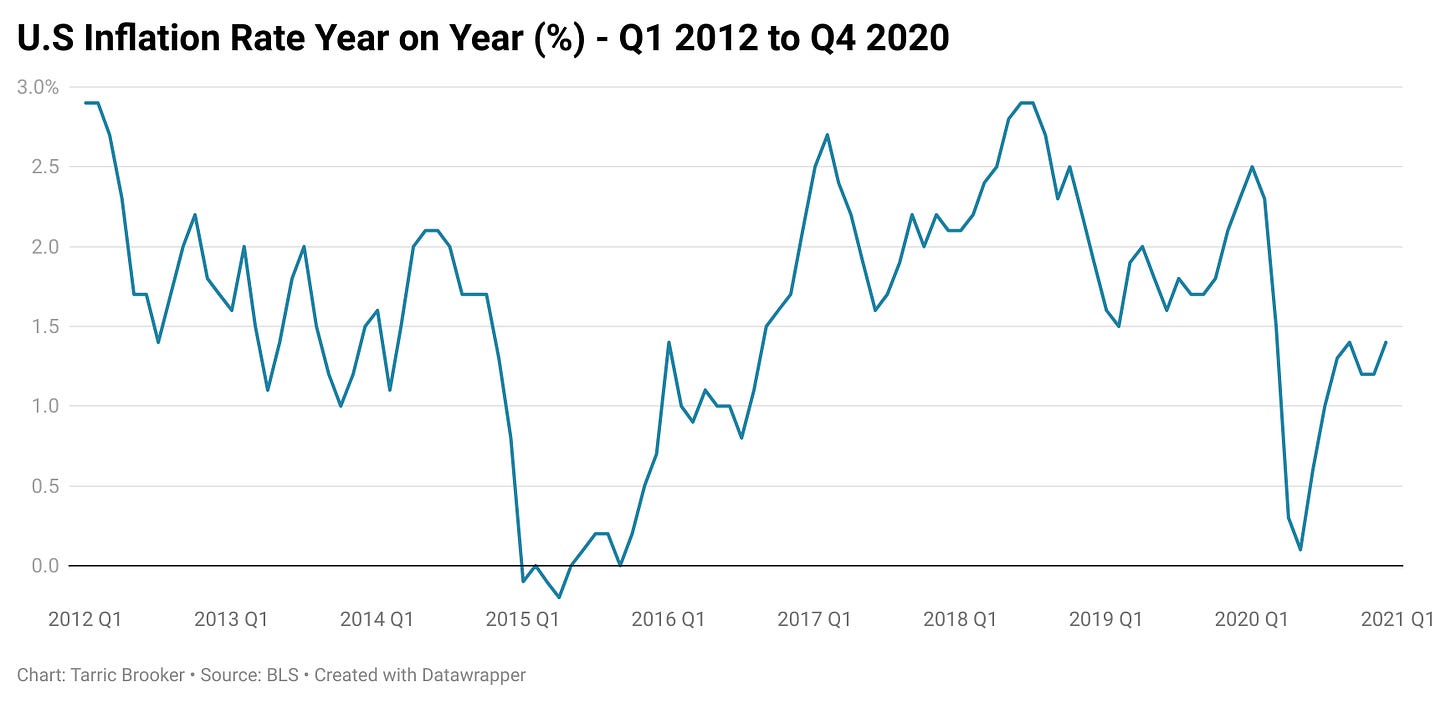

In the 3 years prior to the pandemic, the main driver of broader U.S inflation was overwhelmingly services inflation.

As you can see from the chart below, food inflation played a minor role and energy made a cyclical contribution to the upside and the downside.

But what is almost entirely missing from the picture is goods inflation. It quite literally provided less than zero upward pressure on inflation, with it actually acting a deflationary factor multiple times throughout this period.

Through a combination of offshoring, technological advancements and hedonic adjustments by statisticians (adjusting for the relative quality of a product), goods inflation effectively became an almost completely benign force in recent years.

The pandemic and the supply chain crisis changed all that.

The decline of global ‘Just in Time’ supply chains

At its heart the ‘Just in Time’ supply chain is a deflationary force in relative terms for companies costs, as well as the broader economy.

Rather than spending sizable resources on the production, shipping and warehousing of large inventories, in the pre-Covid world companies could simply order what they needed, as they needed it and keep costs down.

When looking at some of the data that underpinned global trade, its easy to understand why this presented such an attractive proposition.

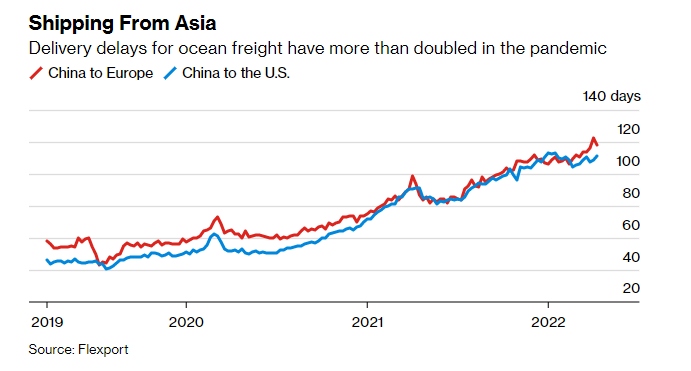

Prior to the pandemic it took just a little over 7 weeks for a shipment of goods to travel from the factory gate in China to the warehouse of a U.S distributor. As of early April, that figure had risen by 117% to more than 111 days from door to door.

With the impact of the current lockdowns in China yet to be fully represented in the statistics and roughly one fifth of the world’s container ship fleet stuck in congestion at the world’s major ports, this figure may rise significantly in the coming months.

As corporates continue to build inventories in response to the broad supply chain uncertainty, the demand for warehouse space has increased significantly, along with the cost of warehousing goods.

For example, in Los Angeles county the cost of renting a warehouse per square foot rose by 28% in the year to the end of Q1, with the sale price of warehouse space rising by 45%.

Between the war in Ukraine, interruptions to supplies of key commodities/components and the impact of the pandemic, its clear that the days of the ‘Just in Time’ supply chain as the defining force in global logistics will in time draw to a close.

In today’s world the risks are arguably too great that a geopolitical event or some other circumstance beyond a companies control could leave it without raw materials, components or finished goods.

Deglobalization and regionalization

As the tectonic plates of global geopolitics continue to shift creating a more uncertain and less stable world, globalization is slowly reversing and being replaced by the regionalization of supply chains and reshoring of manufacturing capacity.

Perhaps the most notable shift underway is the move away from U.S companies producing goods in China.

According to the 2021 Kearney Reshoring Index, 79% of manufacturing executives of companies who have operations in China have either already moved part of their operations to the United States or plan to do so in the next year. With an additional 15% evaluating the possibility of similar moves.

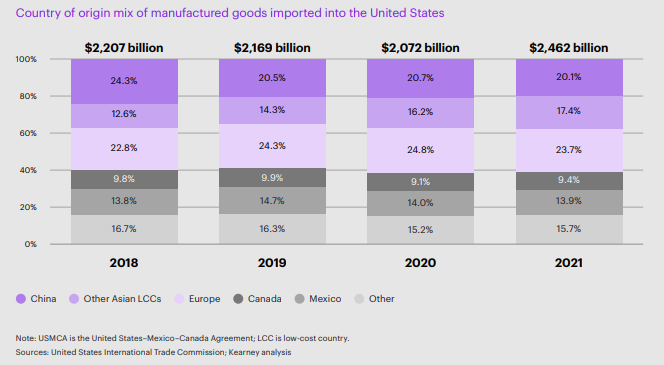

Despite the explosive growth experienced in the U.S imports of goods since the pandemic began, efforts to diversify the supply chains providing manufactured goods to the United States have already begun to have an impact.

In 2018, China accounted for 24.3% of manufactured goods imported into the United States, with other low cost Asian producers providing 12.6%. In 2021, that proportion had fallen to 20.1%, with low cost Asian nations now accounting for 17.4%.

Given the impact of the war in Ukraine and rising concerns over a potential Chinese move on Taiwan, the drive for manufacturers to reconsider their operations in China and the security of their supply chains more broadly has grown significantly.

One can only imagine that this drive will only become more pressing as the world becomes a more challenging and uncertain place.

Entrenching inflationary pressures

While headline CPI inflation may rise and fall for all manner of reasons over the coming years, it can be argued that the long term inflationary pressures stemming from goods have changed dramatically since the pandemic began.

Rather than acting as effectively an inert input or deflationary factor most of the time, goods inflation may become a significant driver of inflationary pressures over a long term time horizon.

For a moment let’s imagine a scenario where goods inflation added just 0.5% to the U.S CPI YoY over the past decade, less than 1/3 of the inflationary pressures stemming from the services sector in recent years.

Under this scenario headline inflation would have been higher than the Fed’s target for all the rate cuts during 2019.

If the forces laid out in this article were to hypothetically have this relatively minor effect on U.S goods inflation when supply chains finally normalize, it may be much harder for the Fed to keep inflation under its 2% target under normal economic conditions.

For much of the 25 years prior to the current inflationary pressures, durable goods were a major deflationary force on U.S inflation, allowing the Fed to run much looser monetary policy conditions than would have otherwise been possible.

With that factor now arguably a thing of the past and moderate goods inflation now potentially here to stay, a more inflationary future is an increasingly likely scenario.

To what degree it will impact headline inflation in the years to come is an open question, but what is clear is that it won’t take much to put the Fed in a very difficult and potentially long term bind.

— If you would like to help support my work by donating that would be much appreciated, you can do so via Paypal here or via Buy me a coffee. Regardless, thank you for your readership.