China - A Snapshot of the Forces Driving the Decision Making and Stimulus of the Middle Kingdom

The at times poorly understood nation faces a number of major social and economic challenges

Since the Evergrande saga first exploded onto the global scene in the middle of last year, the Chinese property sector has at times been one of the most talked about elements playing a role in defining the global economy and markets.

Yet despite its rise to prominence and China’s status as the world’s second largest economy, the Middle Kingdom often remains a profoundly poorly understood part of the global picture.

When the situation at Evergrande really started to go down hill in Q3 2021, there was a relatively prevalent idea that like so many other developers or companies that were considered “too big to fail” that it would be bailed out by the Chinese government.

But it wasn’t.

Then at the start of this year, the narrative turned to stimulus. That in the year of President Xi’s ascension to the lifetime leadership of the Chinese state there would be a huge 2008 style construction driven stimulus program to deliver a backdrop of a strong economy.

Despite continued insistence to this day from some on Wall Street that this stimulus would come, it hasn’t eventuated either.

In both instances, some analysts and markets were blindsided by Beijing’s unwillingness to follow the same script of simply throwing money at problems until they went away.

In October last year, Leland Miller and Shehzad Qazi from China Beige Book summed up how things have changed beautifully in an Op-ed for Barrons:

“A paradigm shift has taken place in how Beijing approaches its economic priorities and management. Many China watchers have missed it because they are relying on a series of misperceptions and flawed forecasts based on China’s old growth playbook.”

Yet despite the likes of China Beige Book ramming home that things were indeed different this time, week after week, month after month, the idea that the Chinese government will return to its previous outsized construction stimulus fuelled growth model remains just as strong.

What’s Really Driving Beijing’s Decision Making

To understand what is driving Beijing to make the policy choices that it has, one needs to look deeper than the oversimplified narratives the Chinese government and industry provide for foreign consumption.

Modern China is facing a number of challenging issues, many of which are arguably considered far higher priorities than a commitment to an arbitrary growth target.

In order to explore this we will be looking at a number of different social and economic issues.

Youth Unemployment Crisis

According to a recent data release from China’s National Bureau of Statistics, the youth unemployment rate is 19.3%. This is roughly double the level of the OECD average and 138% higher in relative terms than the U.S unemployment rate.

At this time in 2018, the youth unemployment rate was a far more normal 10%.

Its worth keeping in mind that this is data from the Chinese government, some of it can be quite decent, other data….shall we say not so much.

Perhaps the most interesting part of this data point is that Beijing is freely admitting that it has a major problem with youth unemployment. Its entirely possible that the problem is significantly worse than the data suggests, particularly given the challenges the past two and a half years of Covid-0 have presented.

As a response to deteriorating prospects, many Chinese youth adopted the motto “tang ping”, which loosely translates to lie flat. In essence it suggests simply letting life pass you by, come what may, just doing the absolute bare minimum.

But as the economic and social progression prospects for large numbers of China’s youth continues to decline, some have adopted a far darker tone and the motto “balian”, which translates to “let it rot”.

“Houses are for living in, not speculation.” - President Xi Jinping

For almost 5 years President Xi has been publicly ramming home this message and it speaks to a number of different issues present within Chinese society.

With the cost of housing so high and it taking so long for a couple to be sufficiently comfortable with their situation to have a child, China’s demographics have suffered even further from their already precarious state.

According to Chinese state media, the population of China is expected to see negative growth before 2025. But if you ask some demographers China’s population began falling as early as 2018.

Then there is the issue of China’s gender imbalance, where by there are significantly more men than women in every age demographic under the age of 40.

With significantly more men that women in these key demographics, there is increasingly the cultural expectation that men seeking a wife should own a home.

This is quite a challenge for young Chinese men, with housing prices in China among the highest in the world on a number of different metrics, some are forced to make major sacrifices to achieve home ownership.

Its unsurprising that some young men are increasingly choosing the “tang ping” option and simply opting out, in something of a rerun of the Japanese Hikikomori phenomenon.

Seeing the writing on the wall, Xi attempted to guide the Chinese property market toward a much less speculative future and one focused on housing being used as a home.

But that isn’t what happened, housing prices continued to grow by an average of around 10% in the years that followed, rising further out of reach for the average Chinese. This has left the Chinese government and the broader economy in a precarious and difficult position.

On one hand, the Chinese government knows it needs more affordable housing to have any chance of somewhat arresting the decline of its already poor demographics and to give young Chinese a feeling that they have more of a stake in society.

On the other, the property sector and associated industry’s account for almost 30% of Chinese GDP and Chinese property is quite literally the single largest asset class on the face of the Earth.

With property accounting for 62% of household wealth, one can only imagine what a housing crash would do to consumer sentiment in a nation that has never experienced anything like it since the foundation of the modern Chinese state.

After assessing their two real options going forward of continuing to inflate property prices or a major correction in housing prices, the Chinese government decided it would choose neither. Instead Beijing is pursuing a strategy of price stability, effectively attempting to maintain property prices broadly where they are, but not providing fuel for prices to go significantly either.

As China expert Michael Pettis recently pointed out on Twitter, no government in history has ever managed to stabilize an asset bubble in this manner for any length of time. But that isn’t stopping Beijing from rolling the dice on this unprecedented attempt to have their cake and eat it to.

The Reality of Chinese Stimulus in 2022

While some are still holding out for the 2008 style wave of construction driven stimulus, the ironic reality is that there is already a major wave of stimulus flowing through the Chinese economy. With the economy hit hard by the pandemic and the ongoing Covid-0 strategy, trillions of yuan are being expended on supporting households, businesses and local governments.

This support has taken many different forms, including tax rebates for households and businesses, loans to struggling state owned enterprises and in some cases experiments with direct transfers of cash to households.

In 2022, the issuance of special local government bonds (bonds generally used for infrastructure) was frontloaded into the first half of the year in order to boost the economy.

Yet in reality we didn’t see a run up in commodity demand or an expansion of steel production to fuel this wave of construction driven stimulus, instead the opposite happened.

Chinese steel output is significantly below 2021 levels and steel mills have often faced selling their production at a loss at times throughout this year.

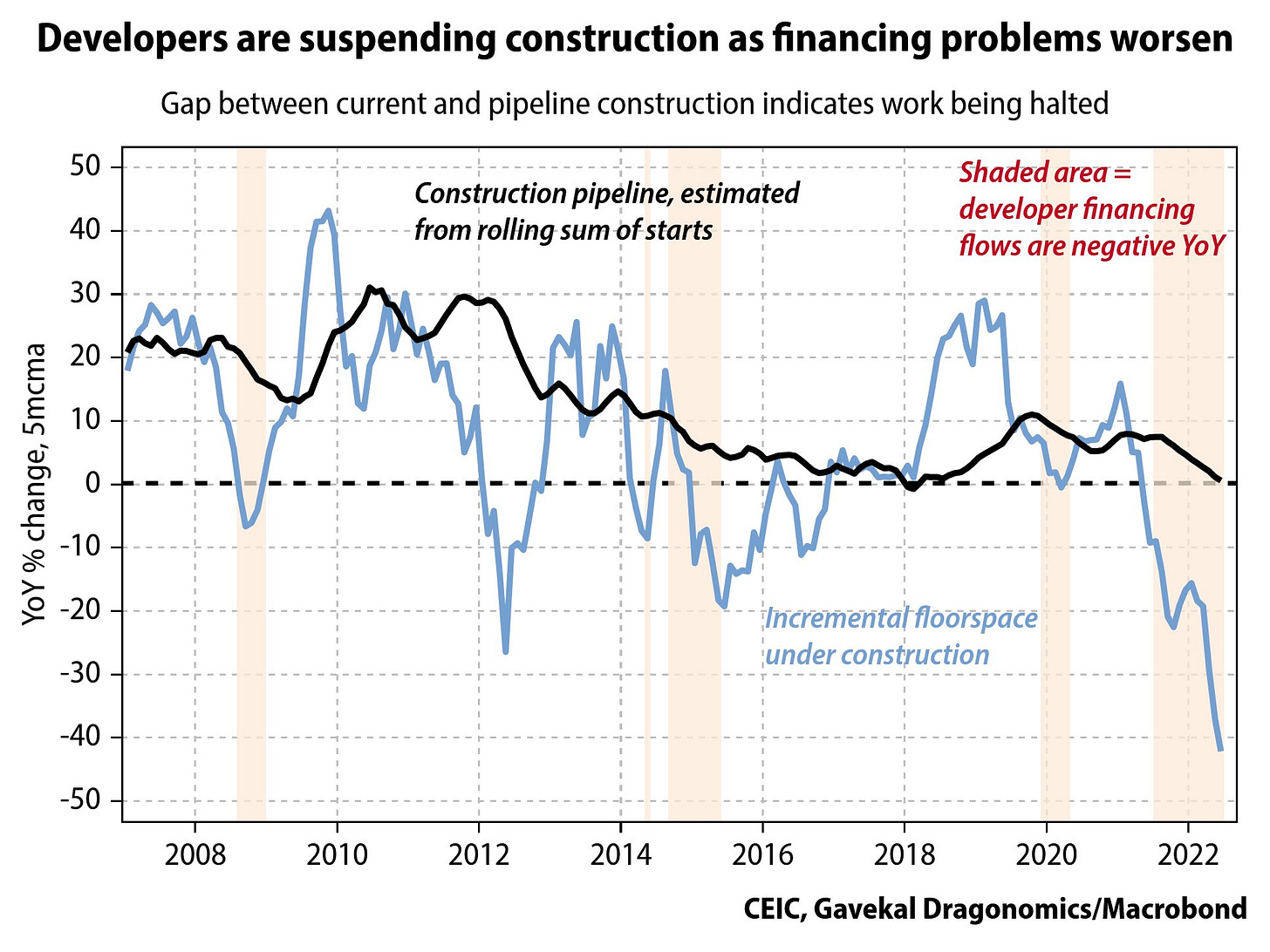

While fixed asset investment is up 6.8% year on year, this expansion has been insufficient to fill the hole left by the deterioration of the property sector. With floor space under construction down by over 40% year on year according to some metrics, even this front loaded form of infrastructure stimulus cannot keep up.

With this years local government special bond issuance already effectively concluded, its now being considered that 2023’s issuance should be brought forward to 2022, ostensibly to kick start the economy.

The often overlooked reality of the Chinese economy and stimulus programs is that several local governments are effectively up the creek without a paddle in terms of debt. With local governments deriving an average of around 40% of their revenue from land sales to property developers, the ongoing woes of the property sector has blown a major hole in their revenue base.

Amidst this highly challenging environment, the provinces of Hebei, Hainan and Liaoning recently requested that the central government in Beijing raise their debt quotas.

This illustrates the issues with Chinese stimulus programs going forward quite well. While the intention may be for bond issuance to drive infrastructure spending and broader growth, with so many local governments in dire straits due to a deteriorating property sector and the impact of Covid-0, an increasingly large amount of resources will need to be dedicated to propping them up.

But The Narrative Said…

Not a week goes by without some form of announcement from the Chinese government or a new bullish narrative on how this time is really going to be different in terms of stimulus or Beijing backing off on intervention with large Chinese corporates.

But as anyone paying attention will tell you, what the narrative says and what ends up being enacted in reality is often two completely different things.

Take the recent announcement of a 300 billion yuan ($44 billion) fund from the People’s Bank of China (China’s central bank) to help property developers complete projects.

In less than 48 hours that narrative evolved to 1 trillion yuan ($148 billion) in funds to support property developers. But when you read the fine print it becomes clear that the reality is quite different. The People’s Bank of China will provide 300 billion yuan to commercial banks, to then leverage into 1 trillion yuan worth of loans to the property sector.

But with the sector in such dire straits banks are going to be extremely reticent to lend to anyone but the best borrowers or state owned developers. Unless Beijing effectively orders banks to lend, its unlikely these funds will reach the developers who need them the most.

This is a nice illustration of how narratives surrounding the Chinese economy function, there is an impressive headline, the associated market moves, but the reality that ends up playing out ends up being far different.

A recent example of this is the repeated commitments by Beijing to get commercial banks to lend to small and medium businesses impacted by the pandemic. The support is there from the central government to do so, but given the risks commercial banks remain understandably reticent to lend.

Despite Beijing pressing for more credit creation for small and medium enterprise, it isn’t eventuating as credit remains as tight as ever. Meanwhile, for businesses that are getting the loans they need, interest rates have risen for the fourth quarter in a row even though the People’s Bank of China continues to cut benchmark and mortgage rates.

A Reality Check and the Property Sector

Despite the numerous different narratives surrounding the Chinese economy, the reality is often right there below the surface.

Ultimately, China faces a number of profound challenges that will not be easily addressed or fixed, they will continue to define the priorities of the central government and impact the decisions of policymakers going forward.

While observers may see a 2008 style stimulus binge as the fix for what ails the Middle Kingdom in the short to medium term, the reality is far more complex. Simply building more roads or railways isn’t going to get couples into home ownership or give young people a feeling that they have a stake in society.

Nor will it fix the serious demographic issues which may ensure that growth slows significantly as China fails to get rich before it gets old.

Meanwhile, the controlled demolition of the property sector continues, as Chinese policymakers attempt the unprecedented task of stabilizing property prices at a high level.

In a lot of ways the challenge Chinese policymakers face is akin to a circus act where a performer needs to keep a large number of plates spinning.

In the past, Beijing was able to pursue economic growth as a near singular objective as a rising tide lifted all boats in society. But as strong economic growth becomes harder to come by and social issues become far more major factors to a degree not seen in over 30 years, policymakers face a major challenge.

China may be the second largest economy in the world, but at a domestic level there is increasingly fierce competition for limited resources. Households, businesses, local government, banks, property developers and more are all competing for government assistance, and ultimately some are going to have to go without.

The challenge policymakers face in this regard has been abundantly clear for quite some time now. Over time the response of policymakers has evolved from reductions in spending on state owned enterprises and government offices to now when there isn’t enough resources to bailout depositors at local banks when they get caught by a bank run.

This competition for limited resources is arguably one of the most overlooked elements of some mainstream commentary on the Chinese government and by extension the broader economy.

While China may seem like an economic juggernaut with bottomless pockets to the casual observer, its government has a lot of commitments to keep in order to maintain its own power and the cohesion of Chinese society.

In time hard decisions will need to be made, but in the short term the decision making process is arguably a far more easy one. When faced with a choice between pursuing a 2008 style stimulus that would send commodity prices rocketing or supporting households, businesses and local government, its clear what the smart decision is.

Whether Beijing can continue to make the smart decision in the face of a concerted campaign by vested interests and increasingly frustrated asset holders who bet big on rising prices, that may be quite another matter.

— If you would like to help support my work by donating that would be much appreciated, you can do so via Paypal here or via Buy me a coffee.