Australia's Deep Reliance On China In Charts

Exactly how much does the Aussie economy rely on China?

I have discussed this issue in great detail on podcasts in recent months with the great folks below if you want to have a listen.

Mayhem and Markets and Ayesha Tariq

When the Chinese government imposed various punitive trade actions on the overwhelming majority of Australian exports to China in 2021 (by industry, not value), there were serious concerns this could be a major blow to the Australian economy. But in the end the impact ended up being far more bark than bite.

This was largely down to Australia’s mineral exports being left mostly untouched by the various trade actions, with the exception of thermal coal exports.

Over time Australian produce found different export destinations and in the case of thermal coal, ended up backfiring on Beijing as the market dislocation driven by Beijing’s import ban arguably played a role driving prices higher and left Chinese power stations with significantly lower quality coal.

2022 also brought other lessons for Australia’s economy. Despite China putting a majority of its cities into a protracted lockdown and many industries suffering quite badly, the Australian economy really wasn’t worse for wear.

This is perhaps the key point in all of this, Australia’s economic fortunes are not directly reliant on the broader Chinese economy, but instead deeply dependent on a select few industries that represent the vast majority of China derived export revenue.

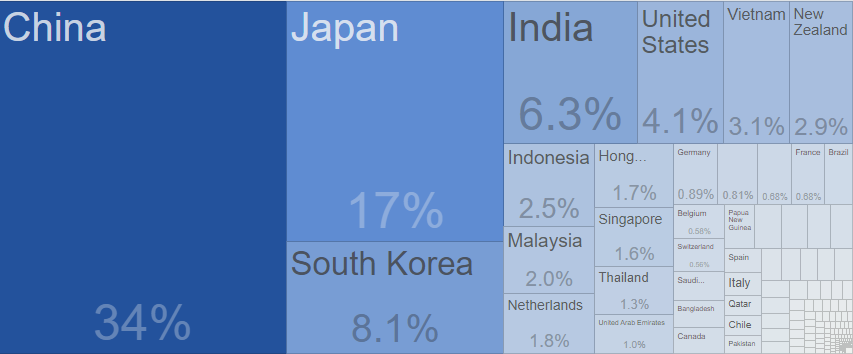

In 2022, China accounted for 34% of Australia’s total exports, more than the next three nations put together (Japan, South Korea and India).

But Australia’s reliance on China goes deeper than this figure would suggest. As by far the largest importer of raw industrial commodities in the world, it is ultimately Chinese demand which is often the defining characteristic in determining prices.

Even rumours of a construction intensive stimulus program can assist selected commodity prices such as iron ore or coking coal in levitating above levels what might otherwise be considered consistent with broader fundamentals.

The Hard Numbers - Iron Ore

Of the total exportable supply in global iron ore markets, China buys up a little over 70% of the market. The next largest importer is Japan with 7.3% of total imports.

On the other side of the coin Australia is the world’s largest exporter of iron ore by a huge margin, accounting for 53.6% of global exports. This illustrates nicely the symbiosis between China and Australia, China couldn’t hope to buy enough iron ore to meet its needs in the rest of the world combined, while Australia could never find enough demand to meet its supply if China were to withdraw its purchases.

Even a doubling of purchases by the 2nd largest importer, Japan, would not make up for even a 10% drop in overall Chinese demand, part of this is due to large domestic supplies which help to supply the Chinese steel industry.

The Dirty Business - Coal

When it comes to metallurgical coal or coking coal as its also known, its a somewhat similar story. China consumes almost double as much as the rest of the world combined. But unlike iron ore, much of China’s supply is either secured from its neighbours or domestically.

But with China the largest consumer of coking coal by far, its demand ultimately heavily influences global prices. With Australia once again by far the largest exporter in the world, the fortunes of global steel demand are once again key to Australia’s economic future.

What Does Australia Get Out Of It?

In short, quite a lot.

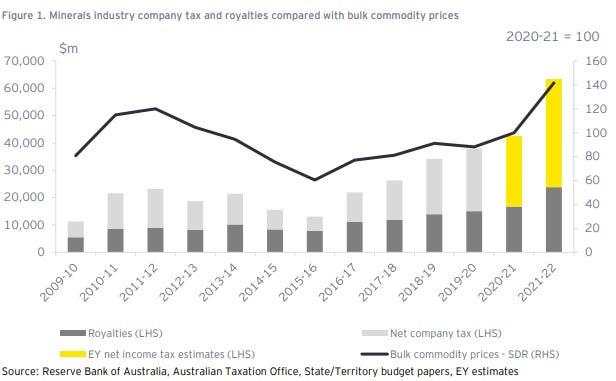

It was recently estimated that during the 2021-22 financial year the mining sector would drive around $63 billion in revenue for federal and state/territory governments. At a bit under 3% of GDP, these inflows have proven to be quite a boon to the bottom line of the federal Treasury and those of states and territories with significant mining operations on their soil.

The enormous inflows that the exports of the resources prompt into Australia also help the nation to derive a significant trade surplus, despite some of its closest rivals in the economic complexity stakes being Uganda and Namibia.

Can Indian Demand Help Rescue Australia?

As the diplomatic relationship between New Delhi and Canberra grows closer, some have raised the prospect of India replacing China as the go to destination for Australian bulk commodity exports.

This chart illustrates nicely that India is on a very different path, one of far greater self sufficiency than China. India’s imports of iron ore are minimal and in some recent years it has been a net exporter of iron ore.

Despite being the largest importer of Australian coking coal, domestic Indian coking coal production is currently growing at a faster rate than the Indian steel industries requirements. According to the latest data India imports 56 million tons of coking coal per year and produced around 54.6 million tons.

The Indian Ministry of Coal has been given a target of 105 million tons of coking coal output by 2030 to reduce US Dollar outflows. While this would not eliminate the need for imports of Australian coking coal, if realized it would significantly decrease India’s requirements compared with the current level of imports.

The Outlook For Australia’s China Fortunes

Going forward Australia finds itself closely watching Beijing’s balancing act, as China attempts to offset the impact of a tanking property sector with additional infrastructure spending and other forms of fixed asset investment.

With total real estate under construction currently down 16.1% since its peak, so far Beijing has managed this balancing act relatively well.

With a still relatively decent pipeline of projects that still need to be completed, so far the Chinese construction sector and the economy’s like Australia that rely on it have mostly dodged difficulty up until this point.

Through the continued increase in fixed asset investment, much of it in infrastructure with a business and productivity case that is insufficient to justify its construction, the Chinese government has managed to buy time.

This is perhaps one of the most underappreciated aspects of the current state of the Chinese economy. The “stimulus” is actually already here, the problem is its offsetting weakness in the property sector, so its not really all that stimulatory, if at all.

But as the pipeline of projects slowly dwindles and total real estate under construction continues to fall toward the drop in housing starts from their peak, the balancing act becomes ever more challenging.

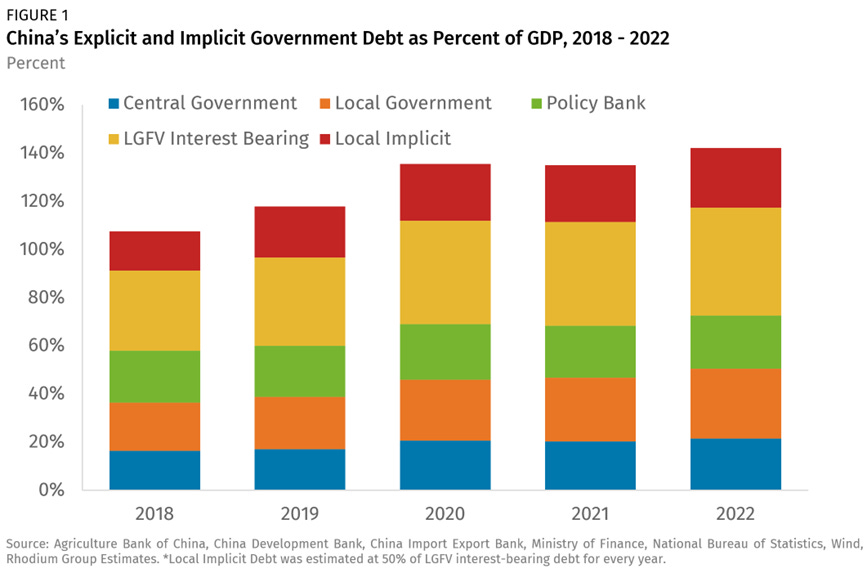

In more recent history much of Chinese infrastructure has been funded by local government, but with local government debt loads at extremely high levels in aggregate, that option is slowly being eroded in province after province, as local governments feel the pinch.

While the current status quo is likely to continue for a while to come, the clock is ticking. Local governments can only take on so much debt before there needs to be a reckoning of some variety. Whether its a bailout of local governments from the central government in Beijing (likely with all manner of strings attached), forced asset sales or something else entirely, the issue of local government debt will eventually need to be addressed in some form.

As for Australia, it is reliant on Beijing continuing to support the construction sector and not allowing steel demand to fall to such a degree that it begins to significantly undermine commodity prices. While the federal budget has prices at significantly lower levels pencilled in, the reality of lower levels of commodity driven revenue than in recent years would be quite a blow to state and federal Treasury’s, especially at a time when the domestic economy is already in a recession in per capita terms.

Ultimately, this is something that will play out of a long period of time, bar some sort of crisis rapidly accelerating the timeline. Australia doesn’t have a plan B and it remains to be seen what Beijing’s plan is. But what is clear is if the calls of Chinese steel production peaking in 2020 are correct, Australia faces a very different next 20 years when compared with the last two decades, where Chinese commodity demand has always come to the rescue at the right time.

— If you would like to help support my work by making a one off donation that would be much appreciated, you can do so via Paypal here or via Buy me a coffee.

If you would like to support my work on an ongoing basis, you can do so by subscribing to my Substack or via Paypal here

Regardless, thank you for your readership and have a good one.

Great article and thanks for aggregating all this information in one place.

Great to have the position clarified. Thanks very much.

Let me recommend this: https://www.gingerriver.com/p/full-text-chinas-plan-to-make-fujian

An insight into a different way of doing things to what we are told to expect from a totalitarian regime.