A Data Driven Snapshot Of The Falling Australian Property Market

Weighing the impact of immigration and low stock levels against market headwinds

As the year draws to a close, the Australian property market finds itself in deeply unfamiliar waters, experiencing the swiftest fall in housing prices seen in decades.

Under more normal circumstances, this is usually when the Reserve Bank cuts interest rates or the federal government throws some form of policy at the market to stimulate demand for housing. But in this instance high levels of inflation are preventing that from happening, at least for now.

Without intervention and with borrowing power falling rapidly, housing prices on a 5 capital city aggregate basis are falling faster than those of the United States during the global financial crisis recession.

But like all housing downturns, it hasn’t been an entirely linear drop in prices. In October and November price falls in Sydney and Melbourne began to slow somewhat, leading to calls from some quarters that the market would soon turn upward.

As I covered in a previous article here on Substack, this was likely a case of seasonal support for the market which has now faded.

Factors Supporting The Market? Immigration And Low Stock Levels

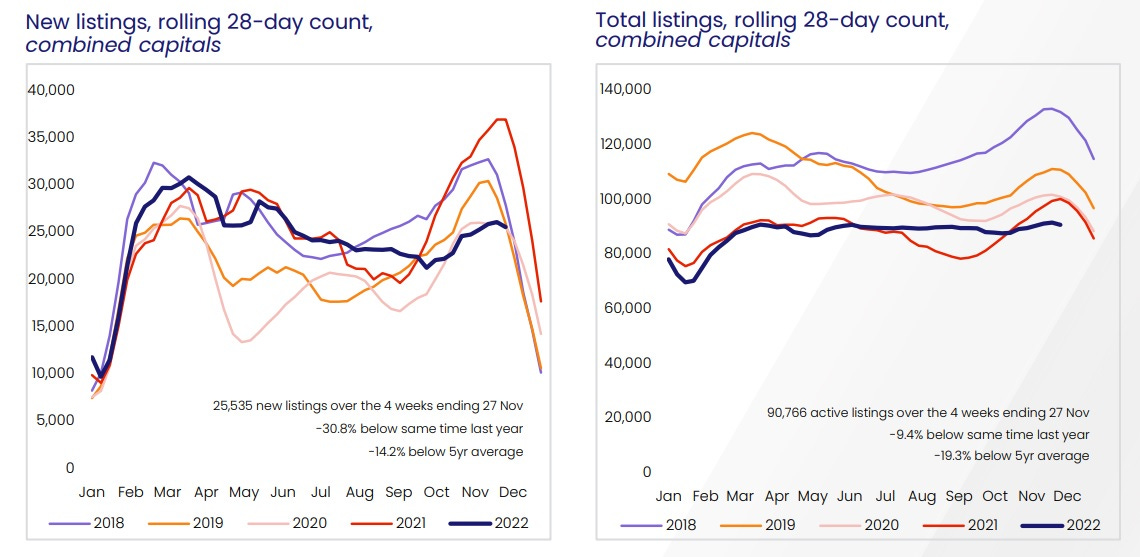

Amidst these sizable price falls, its worth noting that some of the underlying fundamentals were actually providing a great deal of support for the market. New listing volumes for the normally busy spring selling season were at their lowest level since at least 2010. The complete lack of a seasonal ramp up in listings which normally occurs this time every year was also a factor supporting the market, but wasn’t enough to stop prices from falling.

As a result of this low number of new listings, the number of homes listed for sale has plummeted to stand well below even 2020 levels, when the market was heavily impacted by the pandemic.

There is a theory that immigration (non-humanitarian permanent intake) ramping up in 2023 to its highest level in Australian history could help support the property market, but when you look at the data it becomes clear that its not the silver bullet solution it may appear to be.

According to a 2006 study commissioned by the Federal Treasury, in their first 2 years in Australia 7% of new migrant households purchase a home outright, while 12% get a mortgage to buy a house. If we extrapolate that figure on to the current permanent migration intake at the same household size as the current median, permanent migration creates demand for around 14,000 homes or roughly 3% of current annual turnover.

While demand for an extra 14,000 homes per year is arguably a significant factor when compared with 2021, the increase over pre-Covid levels of immigration driven home demand is far less impactful. However, in terms of Australia’s extremely tight rental market, the almost 70% of new migrants that rent on arrival will put greater strain on the supply of homes.

The Other Side Of The Coin - Fixed Mortgage Cliff And Rising Debt Servicing Costs

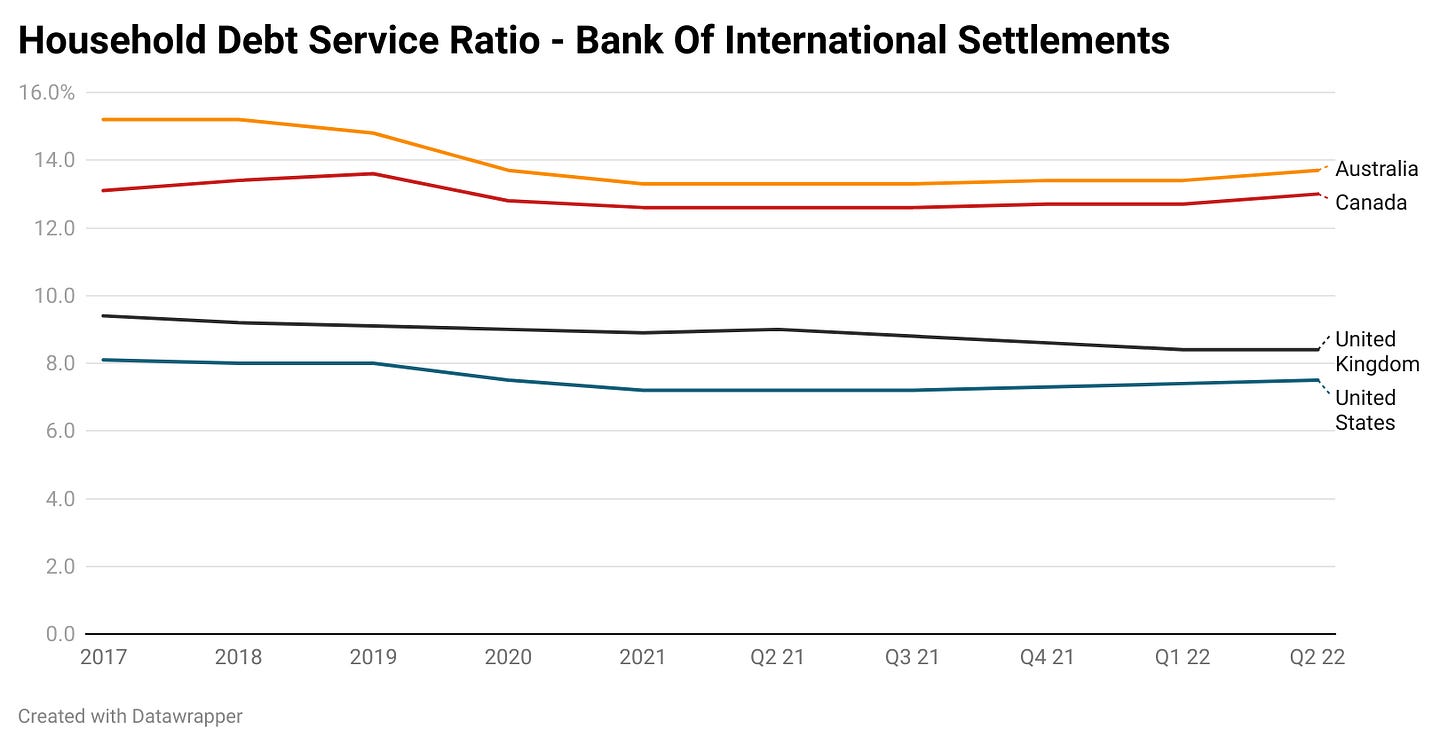

According to data from the Bank of International Settlements, even when Australia had a cash rate 0.35%, it had the highest household debt servicing ratio of all the developed world nations that the BIS data covers.

With household debt servicing taking up 13.7% of household income in Australia during Q2 2022, Aussie households spend 82.7% more of their income on servicing debt than their American counterparts.

Currently Australia’s closest rivals are South Korea and Canada, where households spend 13.4% and 13.0% of household income on debt service respectively.

But this is not an entirely balanced comparison. In Canada and South Korea rates had already risen by a far larger amount by the end of Q2 2022 (0.75% and 1.25% respectively), whereas in Australia the RBA had only raised rates by 0.25%.

As the full scope of rising interest rates is factored in, Australian debt servicing costs as a percentage of household income will hit all time high’s.

Historically roughly 85-90% of Australian mortgages have been on variable rates, but the pandemic changed all that. After the RBA provided $188 billion in capital to the banks at just 0.1% over 3 years, it was suddenly possible for 3 year fixed rate loans to be written at sub-2% rates, a previously unprecedented low in mortgage rates.

By the time the fixed rate mortgage frenzy came to its peak in April, around 40% of Australian mortgages were on some form of fixed term.

According to data from Westpac, over the course of 2023 a bit over 46% of those fixed rate mortgages at the bank will roll onto much higher variable rates. Based on the current average variable rate payable data from the RBA and adding the two latest rate rises, these borrowers would be rolling off onto variable rates of roughly 5.6%, provided rates aren’t raised further in the new year.

For borrowers who took out loans at around 2% or less, this is going to be quite the shock to the household budget. While I suspect that a solid proportion are already preparing for this eventuation, there remains the widespread belief that the RBA and the government won’t allow anything bad to happen, and that they will ride to the rescue if it becomes needed.

Considering decades of precedent, this standpoint is well and truly backed up by past events, but whether or not that will be the case in 2023 amidst decades high inflation is another matter entirely.

While it would be extremely risky and arguably quite foolish for the RBA or government to intervene in a high inflation environment, in Australia this type of action cannot be ruled out.

The Takeaway

Ultimately, falling borrowing power and the increasing likelihood of deteriorating economic conditions are likely to continue to support further falls in property prices. While immigration ramping up and low levels of stock on the market will provide some support for the market, these tailwinds alone are likely to be insufficient to offset broader weakness.

2023 looks to be a challenging year for Australia, as household debt servicing costs hit all time record highs and more than 16% of borrowers face their mortgage repayments potentially doubling or even tripling, as fixed rates roll off on to much higher variable rates.

As we close out the year, I want to wish you all a Merry Christmas, a happy holiday season and a joyous new year.

Thank you for your support and readership throughout 2022.

— If you would like to help support my work by donating that would be much appreciated, you can do so via Paypal here or via Buy me a coffee. Regardless, thank you for your readership.

If you would like to support my work on an ongoing basis, you can do so here via Patreon or via Paypal here

Hi Tarric, interesting read! What would be an example where someone's repayments would double? and what would be one where they would triple?